Project Recover located the Arnett B-24, tail number ‘453, in January 2004 after ten years of searching. The find led to the repatriation of eight crew members who went down with the plane on September 1, 1944. Three crew parachuted out. It is possible they were captured and executed by enemy forces. They remain MIA.

First, a point of clarification. You may see an aircraft referenced in any one of three ways.

- The pilot’s last name and the plane type, ie. Arnett B-24. This is a customary practice to distinguish between the sheer number of missing aircraft and crew.

- The last three numbers of its serial number or tail number, which was 42-73453. (the Arnett B-24 is also known as ‘453) and/or

- Its nickname (the Arnett B-24 did not yet have one)

Arnett B-24: Crew & Mission

On September 1, 1944, the Arnett B-24, with the tail number ‘453, took off on a mission to bomb enemy targets in Koror, Palau. The crew had not been together long. They had yet to nickname the plane. They considered “The Big Stoop” after both the big, friendly navigator, 2nd. Lt. Frank J. Arhar, and a well-known movie character of the era.

Following is a list of the crew members who were on the ‘453 that day. Three regular crew members were substituted for the mission. The youthfulness of the crew, although perhaps not unusual, is notable. Their average age was 21 years old.

- 2nd Lt. Jack S.M. Arnett, 24, Pilot, Friendly, WV

- F/O Willaim B. Simpson, 22, Co-pilot, Winston-Salem, NC

- 2nd Lt. Frank J. Arhar, 22 or 23, Navigator, Lloydel, PA

- 2nd Lt. Arthur J. Schumacher, 21 or 22, Bombardier, St. Louis County, MN

- TSgt. Robert J. Stinson, 23, Engineer, San Bernardino, CA

- SSgt. Jimmie Doyle, 25, Nose Gunner, Lamesa, TX

- TSgt. Charles T. Goulding, 21, Radioman, Marlboro, NY

- SSgt. John Moore, 19 or 20, Asst. Radioman, Des Arc, AR

- SSgt. Earl E. Yoh, 20, Gunner, Van Wert, OH

- SSgt. Leland D. Price, 22, Tail Gunner, Defiance, OH

- Sgt. Alexander R. Vick, 28 or 29, Photographer, Campbell, CA

Arnett B-24: The Mission

On Friday, September 1, 1944, at 6:30 am, eighteen B-24 Liberators took off from Wakde Island. They were heading in a northeasterly direction toward Koror, Palau, more than 700 miles away. A loaded B-24 had a max speed just over 250 knots and it would take the B-24s about four hours to reach their targets.

There were six B-24s from each: the 371st, 372d, and 424th Bombardment Squadrons all in the 307th Bombardment Group. The ‘453 was with the 424th Squadron. The plane fell into formation with 14 other B-24s, leaving three B-24s on a reconnaissance mission first to form their own flight. The planes flew in trail, ‘javelin down’ within squadrons.

They approached their enemy target at 17,000 feet with clear visibility. Just as the Arnett B-24 was over their target, they took two direct hits on their left-wing. Their number two engine burst into flames. The crew immediately salvoed the bombs and slid out of formation. At least two crew were seen parachuting out. Lt. Arnett banked right in an apparent attempt to put out the flame, but the left-wing folded and broke off of the airplane. The plane spiraled out of the sky, breaking the fuselage in two and crashing into the sea.

The Squadron Leader circled back around from Babeldaob in time to see a boat nearing Koror Islands leaving a wake behind it. The wake led back to the spot where the first parachutist landed.

All 11 crew members were declared Missing in Action. In one year and one day, they were officially declared Killed in Action. Their families carried the loss. They shouldered the numbing burden of not knowing. When the MIAs’ parents, siblings, and spouses died, their unsubsiding grief was passed unknowingly and unintentionally to future generations.

50 Years Later: The Search Begins

Fifty years later, Pat Scannon made it his mission to find MIAs and help bring them home. In those days, he focused exclusively on WWII MIAs lost in Palau. In 1994, he became intent on finding the Arnett B-24 and helping to bring the MIAs home.

Pat had the Missing Air Crew Report (MACR) for the Arnett B-24. It told about the 307th Bombardment Group’s mission on September 1, 1944. Most importantly, there was a map. An X marked the spot where the plane went down.

Pat was optimistic. The map indicated the plane was off the south part of Palau’s big island, Babeldaob. in about two square miles of enclosed waters. Pat was just beginning to learn how to accomplish this, legally, ethically, while working in full cooperation with the Palauan and United States governments.

He figured that finding a plane in relatively well-defined waters was the place to start. Success seemed not far away..

But it turned out it would take a long time.

Multiple missions spanned multiple years. The fledgling team dove the couple square miles using the very best of the most rudimentary equipment: scuba diving in grids.. They searched the entire area over and over again.

After an article appeared in Parade magazine on Memorial Day Sunday in 2000, the son of SSgt. Jimmie Doyle, the nose gunner with the ‘453 aircrew, contacted Pat, seeking information about their long missing airman. During a 307th Bombardment Group reunion in Texas, Pat met with Tommy Doyle and his wife, Nancy. They became fast friends and have stayed in close contact with them to this day.

Over and over again, they found nothing.

“You would have thought there would have been a Chevy engine, an old car, or something,” Pat said. “But we found nothing.”

More Searching, No Results

Pat Scannon was beginning to learn how big of a job bringing home MIAs was. He conducted research at the U.S. Air Force Historical Research Agency at Maxwell AFB in Alabama. He went to the National Archives in both Suitland and College Park, Maryland. He had all the information. He even started learning how to skydive and pilot a plane to better understand what the WWII aviators he was searching for felt.

“How can we be missing this?” Pat thought as they searched the area yet again.

One of his friends suggested they use a towed underwater magnetometer. A B-24 engine would surely set it off – and a B-24 had four engines. The team used it. They even got a signal.

Still, they found nothing.

Pat wrestled with disappointment. He wanted to find the crash site so he could find the crew. He wanted to help bring them home. Plus, he had men and women volunteering with him. He wanted them to succeed, too.

A WWII Mapping Error?

Finally, in 2002 or 2003, Pat and the team got the ‘bright idea’ that maybe there was an error on the map. This wasn’t unheard of. In 1993, Pat and a different team of divers located a Japanese trawler shot down by then Ensign George H. W. Bush in 1944. They succeeded where others failed because they realized the World War II mapping error.

In his eight year search for the Arnett B-24, Pat had been following a map from the Missing Air Crew Report (MACR).

“The map was very small, the size of a thumbnail,” Pat said, “but I figured they were there, and I was not.”

After so long with no results, Pat finally decided to start at the northwestern tip of Koror and begin searching northward on the west side of Babeldaob. Pat remembered a propeller that he and his wife had seen on the southwest side of Babeldoab in 1993. He hadn’t paid much attention to it at the time and had not thought it could be connected to the Arnett B-24. There were so many planes, so much to learn, so much to do.

However, when Pat decided perhaps there was a mapping error, he thought heading toward this propeller was a good idea.

Still no luck.

Renting a Cessna 206

Pat rented a Cessna 206, a single-engine aircraft, and took pictures of the waters between Babeldaob and Koror. He contacted NASA who suggested taking infrared photographs although these showed no additional information.

He gave a presentation at a reunion for the 307th Bombardment Group. Some veterans who were on that WWII mission so long ago attended. Pat hoped they may recognize a pattern or offer some insight.

They could not. They could remember scattered coral heads, but not enough detail to narrow the search.

The First Sign

The team was eager for a sign they were on the right track. Finally, they got one, sort of. Every member of the team wore a magnetic compass on their wrist. At one point, every compass started spinning. Unknown to them, they were still 400 meters from the crash site, but the strange activity excited and motivated them.

They renewed their commitment to find the ‘453 and hopefully its crew.

Finding the Arnett B-24: Success at Last

In January 2004, Pat and the team returned to Palau. Joe Maldangesang, the Palauan Master Guide and Project Recover team member, unerringly drove the boat to where they left off the previous year.

Joe saw a fisherman paddling a canoe not far away and decided to ask him if he knew of anything. Fishermen in Palau have territories and know their zone intimately. Many are skin divers who easily and routinely dive 50 feet, 60 feet, and even more. Unsurprisingly, Joe’s hunch paid off.

The fisherman pointed and said there were piles of aluminum about 100 meters away.

Pat and the team followed his directions. After ten years of searching plus ten minutes of diving in the right place, Pat and the team finally found the plane.

“We were hugging each other underwater with joy – It is hard to yell underwater!”

They found the front end of the plane: the nose, one wing, and a couple of engines. One of the propellers stuck vertically in the coral head, straight up and down, almost cathedral-like alongside the coral head.

“It was then I realized that the other propeller that my wife and I had found in 1993, which was now only a quarter of a mile away, was a part of this aircraft,” said Pat wondering aloud how the search would have gone had he followed the propeller as the first clue.

Finding the Fuselage

As Pat and the team were investigating and drawing what they found, Joe swam to the backside of the nearby coral head. When he came back, he said in his dry iconic way, “I think you guys should come and see this.”

We followed him. And there was the tail of the plane, the back end of the fuselage. Two things happened next that immediately turned the aircraft from a crash site into a sacred site containing U.S. MIAs.

First, Pat found an open parachute with burn marks on it in the area of the tail gunner. For him, that spoke of someone trying to escape the airplane without success.

Second, Joe found a window with a port or opening for a machine gun. He reached inside and pulled out visible remains from the aircraft.

“Our work is solemn work,” Pat said.

There is a mixture of joy and relief when our MIAs are found. There is also grief as we process the horror of crew members’ final moments and recognize the enduring pain of their loved ones back home.

Through it all, there is an invisible, persistent magnetic attraction pulling the team forward. Over time, we’ve realized our MIAs’ final mission is accomplished when they are returned home. Wordlessly, they speak. Their legacy touches the heart and mind of every American. With it, they give the gift that transcends space and time: love, gratitude, unity, and hope.

As is Project Recover’s tradition, the team held a flag ceremony over the crew’s watery gravesite. We folded one flag for each of the MIAs. Each flag was held for their families as gifts of honor and recognition of the ultimate and enduring sacrifices they have made.

In 2005, Tommy and Nancy Doyle joined the team in Palau to honor Tommy’s father, Jimmie Doyle. The then President of Palau, Tommy Remengesau, Jr., heard of their visit and actually dove with the son, also named Tommy on the crash site, led by Joe Maldangesang and the team.

Families carry the grief of loved ones who are MIA even for those never met. The niece of 2nd Lt. Arthur J. Schumacher, bombardier on the Arnett B-24, accompanied Project Recover on a mission in search of her family’s MIA and others in 2014.

Arnett B-24: Recovery Mission

Project Recover has only recently entered into an agreement with DPAA to begin recovery missions in 2021. In 2004, all recovery missions were conducted by the appropriate government agency.

When Project Recover located the Arnett B-24 in 2004, JPAC (the precursor to Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency) had a team in Palau. They, under the supervision of underwater anthropologist Dr. Eric Emery, began documenting the site for recovery missions. Working with US Navy divers, JPAC conducted three recovery missions spanning 38 weeks over the course of three years, from 2005 to 2008.

Nick Zaborski, who along with John Marsack co-founded Legion Undersea Services and is in partnership with Project Recover to conduct recovery missions, was then a US Navy diving supervisor on the last recovery mission of the Arnett B-24. (Read more about our partnership with Legion Undersea Services.)

“Dr. Emery posted a black and white photo of the B-24 on the dock station just before our first dive,” Nick said. “We all just stopped dead in our tracks and stared for a minute. Like, ‘Wow, these guys really look a lot like us.’ It really put into focus why we were there.”

Early in the recovery, divers had to stabilize the aircraft. Once secure, divers, under the supervision of Dr. Emery, used underwater suction dredges to move the loose sand and debris into baskets held by cables above the wreckage. As these baskets filled, they were then raised to the surface and examined at screening stations.

The MIAa were flown to Hickam Air Force Base in Hawaii in March 2008. By January 2009, eight MIA crew members were identified and accounted for. The three who parachuted out of the aircraft, 2nd Lt. Arthur J. Schumacher, SSgt. John Moore, and Sgt. Alexander R. Vick, remain MIA. At least one Palauan elder recalls seeing these Americans captured and loaded under armed guard on a Japanese military truck, which went north into Babledaob.

Funeral at Arlington National Cemetery

On April 30, 2010, the eight repatriated crew members were buried at Arlington National Cemetery. The then President of Palau, Johnson Toribiong, as well as staff and representatives from the Paluan Senate and Congress, attended the funeral.

The night before the funeral all attendees gathered in a chapel at Arlington. “We know how they died. Let’s hear how they lived,” the chaplain said, and then invited a family member to relate stories about their loved one, now home again.

Each family shared remembrances of their family’s loved one. Memories about the MIAs as boys building model airplanes and gliders and ‘always’ wanting to fly filled the room.

Every memorial service is emotional, but Pat remembers this one as especially so.

“There was not a dry eye. I mean every tissue box was empty,” Pat recalled.

All 11 crew members are memorialized at the Manila American Cemetery on the Tablets for the Missing. The eight recovered airmen now have had rosettes placed next to their names denoting they have been recovered and repatriated home. Some have memorial markers and/or were buried in their hometowns as well.

- 2nd Lt. Jack S. M. Arnett is buried at Friendly Cemetery in Friendly, WV, and has a memorial plaque at Emmanuel Episcopal Church Memorial Garden in Orlando, FL.

- 2nd Lt. Frank J. Arhar is buried at Saint Joseph Cemetery in Beaverdale, PA.

- TSgt. Robert J. Stinson is buried at Riverside National Cemetery in Riverside, CA.

- SSgt. Jimmie Doyle has a memorial marker and is buried beside his wife, Myrle Dean, at Lamesa Memorial Cemetery in Lamesa, Texas.

- SSgt. John Moore has a memorial marker at Lakeside Cemetery in Des Arc, AR.

- SSgt. Earl E. Yoh has a memorial marker at Mohr Cemetery in Van Wert, OH

- SSgt. Leland D. Price has a memorial marker and is buried at Riverside Cemetery in Defiance, OH.

Since 2004, extensive interviews and searches have been conducted in the jungles and hills of Babeldaob attempting to locate the burial site of the three remaining MIAs. No definitive evidence has been located but the searches continue.

The Arnett B-24, its mission, the search for, and stories of individual crew members are featured in:

- The Last Flight Home: a movie co-produced and co-directed by Daniel T. O’Brien. Dan is Project Recover’s Chief Financial Officer and Administrator.

- Vanished: the Sixty Year Search for Missing Men of World War II by Wil S. Hilton was with Project recover when they located the Arnett B-24.

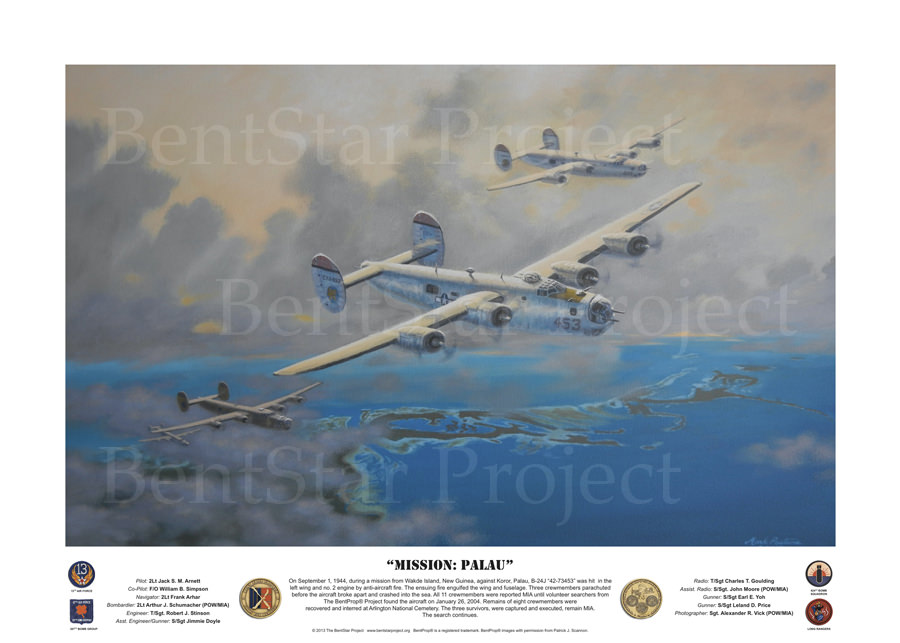

- Mission: Palau, a one-of-kind painting of the Arnett B-24, by Mark Pestana

You can read about our partnership with Legion Undersea Services; a partnership that includes former Navy divers who were on the MIA recovery mission for the Arnett B-24.

Throughout this article my uncle’s name is misspelled. He is the navigator, FRANK ARHAR. Thanks in advance for correcting the record.

Thank you, Cynthia! Corrected. I have enjoyed learning about your uncle and have so much respect for him and compassion for your family’s enduring sacrifice. If you are amenable, I’d like to interview you about him and your family’s experience to learn more. I”ll reach out via email. Thanks again. ~Lauren

tears – – so fortunate to find MIAs for families. I dream and pray to one day find our Families’ MIA.

If you have identified the wreckage of a TBM at Truk correctly (instead of a TBF), I would not believe it was lost during Operation Hailstone. More likely it was lost in the April 29-30 carrier air attacks. If it is a TBM, its probably the Yorktown VT-5 plane piloted by Lt. Richard Upson.

Hi Dan!

Good to hear from you. I am glad you still have your hand in – you are an acknowledged Chuuk expert for sure.

Thank you for your note. The nature of the debris field is that so far we cannot definitively distinguish whether the site is that of a TBM or a TBF Avenger. We also consider other input such as after action last known sightings in attempting to assign a probability as to the possible aircrew. As you know, this is particularly difficult in Chuuk Lagoon because so many Avengers crashed there. But if we do figure out the crash site is a TBF, we will put Lt. Upjohn and his crew high on our list. Thank you for this distinction.

Hope all is well with you!

Respectfully,

Pat

Hi,

I’ve been following Pat & the team since the early days of what was then the “Bent Prop” project, and love this story about the discovery & recovery of the Arnett B-24.

But, one thing confuses me. The article states: “On April 30, 2010, the eight repatriated crew members were buried at Arlington National Cemetery”, but then further below the same article states that Arnett, Arhar, Stinson, Doyle, & Price were buried in their hometowns. Which was it?

Thanks,

Scott

Dear Scott, Thank you for your thoughtful question.

Regarding the burial of the ‘453 crew, actually both burials and ceremonies, one for the entire ‘453 aircrew at Arlington and separate ones for some of the airmen, happened.

When the remains were recovered at the ‘453 underwater crash site, several of the individual remains were commingled, meaning no way existed to separate the remains for individual identification. During the same recovery, some of the remains were located in unique areas that permitted identification. Thus, broadly speaking, two groups of remains existed from the recovery: commingled remains for which identification was not possible and individual remains (not necessarily complete sets of remains) which were identified by DNA and other methods.

Our understanding of the DPAA policy in managing commingled remains is that they are designated to contain remains from all the aircrew, as there is no way to be certain whose remains are specifically commingled.

Another DPAA policy is that each family has the choice of a ceremony at a National Cemetery or locally (eg, a family plot). Some of the families decided to have individual burial ceremonies at home while others decided on the National Cemetery, in this case Arlington. Thus the Arlington burial had a combination of some individual airmen (at the families’ requests) plus the commingled remains, which were placed in a separate casket.

In keeping with the DPAA policy to designate commingled remains to the entire aircrew, the head stone lists all 8 aircrew located (note that the three still missing airmen are not listed). Accordingly, all eight families were invited to the Arlington burial ceremony and most attended.

At the invitations of several aircrew families, members of Project Recover(then BentProp) attended almost all the individual and the Arlington burial ceremonies. Each was very special and we felt privileged to attend.

I hope this helps explain your question, Scott.

Respectfully,

Pat Scannon

Project Recover

Hi Pat,

Thank you so much for that detailed explanation. I understand now, and I’m very glad those 8 families were hopefully able to find some sense of closure after so many years.

I wish you much continued success in your noble mission.

Sincerely,

Scott Cowden