The Solomons MIA Search Mission – What Happened

Solomon Islands, South Pacific: Post three of three. What happened on Project Recover Solomons MIA search mission? Team members included Dan O’Brien (team leader), Derek Abbey (sonar assist), Megan Lickliter-Mundon (archaeologist), Charlie Brown (camera assist), Jeff Lynett (sonar), Ewan Stevenson (Solomon research specialist and guide), Tony Burgess (archaeologist assist), and myself, Harry Parker (photographer).

This post is Part 3 in a 3-part series describing our Solomons MIA search mission. It provides a glimpse of what a mission is like. Although we love sharing our missions with our followers, some of the information from our missions is withheld in order to protect the families and the sites.

Post 1 – Find Solomon Islands MIAs Post 2 – Scuba Diving MIA Crash Sites

Dive Team Arrives in Solomons

After the dive team arrived in the Solomons, it was time to head to our Dive Boat for a week of diving, searching, and documenting. Getting everyone on the boat was a mission in itself. The crew loaded piles of gear and luggage on tender boats. No one knew what to expect. Most of us just looked forward to the food and a cool place to lie down away from humidity after 20+ plus hours of travel time.

Our Dive Boat, Taka, is not just an amazing dive boat, it’s an experience. The dive boat is a complete custom dive setup managed by our host couple Adam and Carman and a cheerful local crew of 11. The crew delivered our luggage to our rooms and gear to our dive stations. After settling in and organizing our gear, we got the full tour.

We went over emergency drills and then sat down to a hot, home-cooked meal. After nearly a week on the road, we had all made it safe and sound. We took time for a quick celebration and some serious planning for the week ahead and our Solomons MIA Search mission.

While Megan, Ewan, Dan, and Tony went over the site, theories on the crashed aircraft and plans of attack, the rest of us headed off to set up our dive gear. Next, we focused on our personal gear, cameras. We had big plans and wanted to be ready. Time flew by, and, before we knew it, we were ready for rest.

Our internal clocks are off by 12 hours or more. When I woke up at 4 AM, I wasn’t surprised to see others up and about, too. The dive boat headed out in the wee hours of the morning. We were treated to a beautiful cruising sunrise with lush tropical islands as the backdrop followed by a delicious breakfast.

In Paradise Local’s Rule

Our dive site is located next to an island filled with several villages. Each village has its own chief. Multiple villages are lead by three elders. To conduct our Solomons MIA search, our team needed permission from the local village. It’s their island, and this team is always committed to fair negotiations and communications. Luckily we have Ewan Stevenson originally from the Solomons with over 20 years as an island resident. Ewan knows the culture and speaks the language. His passion for WWII history and knowledge of the area proved invaluable to our Solomons MIA search mission.

As I gaze out at the island from the boat, it’s hard to tell if the island is actually inhabited or not. The jungles are so lush, tall, and thick. Before we get into our tender to head to shore, one of the elders is paddling to meet us in his hand-carved wooden canoe. We get a smile, a greeting, and permission to come ashore.

The closer we got to shore, the more shore comes into focus. The pristine beaches are covered with huge trees extending far from shore over the water. Leaves are dense and about head high, hiding everything behind them. From the moment we made landfall, we were the spectacle. More children than I could count gathered around, each wide-eyed at the newcomers’ arrival.

Every thatched hut was a work of art. Several huts, obviously dedicated kitchens, billowed smoke of the morning meals. Children laughed, played, and smiled. Parents went about morning chores. And the rest marveled at our arrival. I was struck by the simplicity of community I was witnessing. They had what they needed, their village was clean, well kept and filled with creativity.

I was amazed at the size of the Frangipani trees, the world known flower of the islands. The many species of palms solidified the island feel. The only sign of transportation was the many hand-carved canoes parked on the beach. The kids were obviously happy. The overall vibe was gentle, loving, and chill.

Success in relations

It took a few minutes to get permission to take photos. The vibe was awkward and I hesitated to photograph, not wanting to disturb the ensuing negations much less scare all the children off. They obviously didn’t know what to think of me and my camera.

Once the intros were done, the head chief led us by the water. We sat under the big talking tree where all village business gets done. Ewan explained who, what and why we were there. Once they understood our mission and background, other elders came forth with stories of the original accident from long ago.

They offered new and interesting info about the crash and the survivors. The team was hungry for the info. Some of the information provided missing pieces to the puzzle surrounding the wreck in question.

Back to Basics

Storytelling. It’s originally how info was handed down. Here I was witnessing story-tellers in real time. The stories handed down from the war are very detailed. I could imagine the war raging on these islands where before there was nothing but their peaceful way of life. The details passed down were simply amazing. This Solomons MIA search mission was the better for it.

After about 30 minutes the kids loosened up allowing me to take a few pictures. Some loved looking at the images on the back of the camera. Still, most kept their distance, not knowing what to make of us. As much as the grown-ups tried to shoo the children off to school, they would make their way back around the big tree and end up right back in the circle again. We were the big distraction.

More local villagers moved in closer. I could feel the hesitation. No one was sure who we were and they seemed reluctant to get too close and too curious to walk away.

I was lucky enough during the conversation to get one-on-one time with an Elder. He enjoyed giving me a rundown of their village. Over 40 families lived in this one village. He proudly pointed out the middle schoolhouse, home to over 120 young students. The new high school housed 60 plus high school students. They had a large grassy playing field for the kids. The best part was learning how they governed themselves. He shared what the main issues were and how the villages resolved them. His pride was infectious. The overall feeling of peace, content, and a no-stress communal environment was evident.

As the conversation under the talking tree deepened and came to a close, permission was given to anchor the Taka near the village’s reef and the team to dive the MIA site. We slowly made our way back to the dive boat. It was a beautiful experience. As my feet left shore, I wondered if I would stand on the island again.

Getting Started

As with any mission, this Solomons MIA search is committed to safety. Our first dive was no more than an orientation. This gave us time to come up with our mode of operations and dive buddy communications. We moved some dive stations around and then made a no pressure, no work dive before we picked up our working equipment.

We made three dive teams, sonar, archeology, and camera teams. Each held a specific role and mission. Not all of us could be on the wreck at once, so we cycled through the teams. Every dive got easier as we settled into our routines.

Charlie and I were the camera team. We always jump in first or second with the sonar team. Derek and Jeff were sonar team. They searched around the main aircraft crash site for potential additional debris from the aircraft. Our camera team needs to be the first down in order to get the best visibility. The other teams always have the potential to stir up sediment as they survey the aircraft and surrounding area.

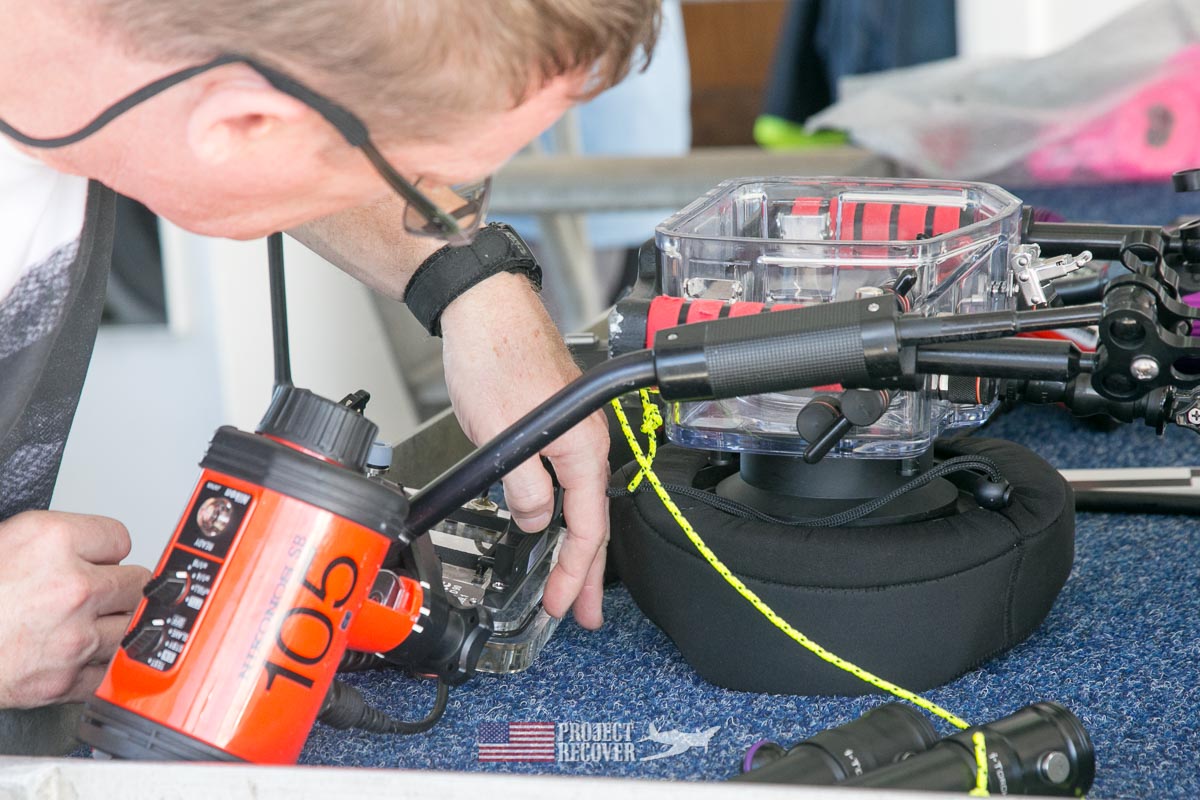

The technology plus scuba diving created some of the biggest challenges. Electronics don’t like travel, humidity, or salt water. Software glitches, cameras malfunction, and the list goes on. Each team went through a dive master lead checklist and a team checklist before the dives. One for diver safety and the other for equipment operations. Getting in the water totally prepared and ready is crucial for success.

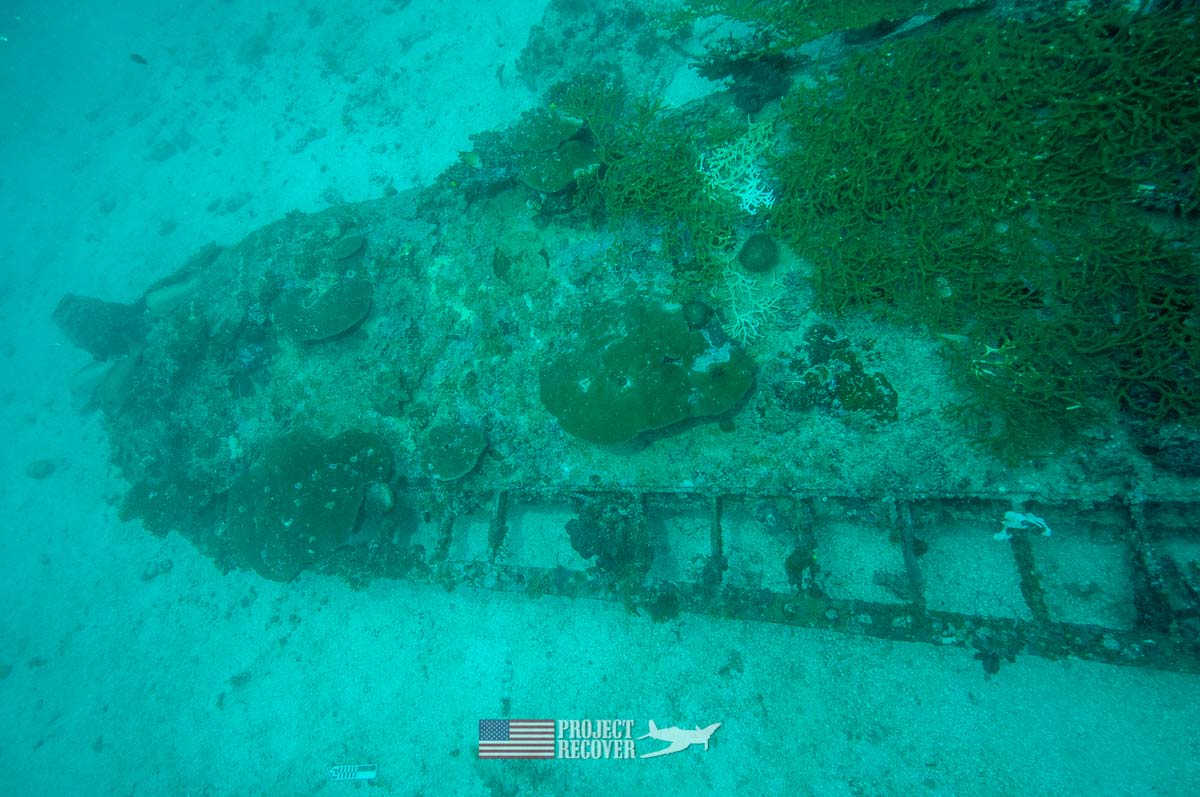

By the first day’s end, the sonar team established a firm grip on the sonar and quickly expanded searches into deeper water. The archaeology team moved through their priority list and formulated key aspects for themselves and a battle plan for the camera team. Our camera team successfully captured one wing ready for 3D modeling and made slight pattern changes for wing two.

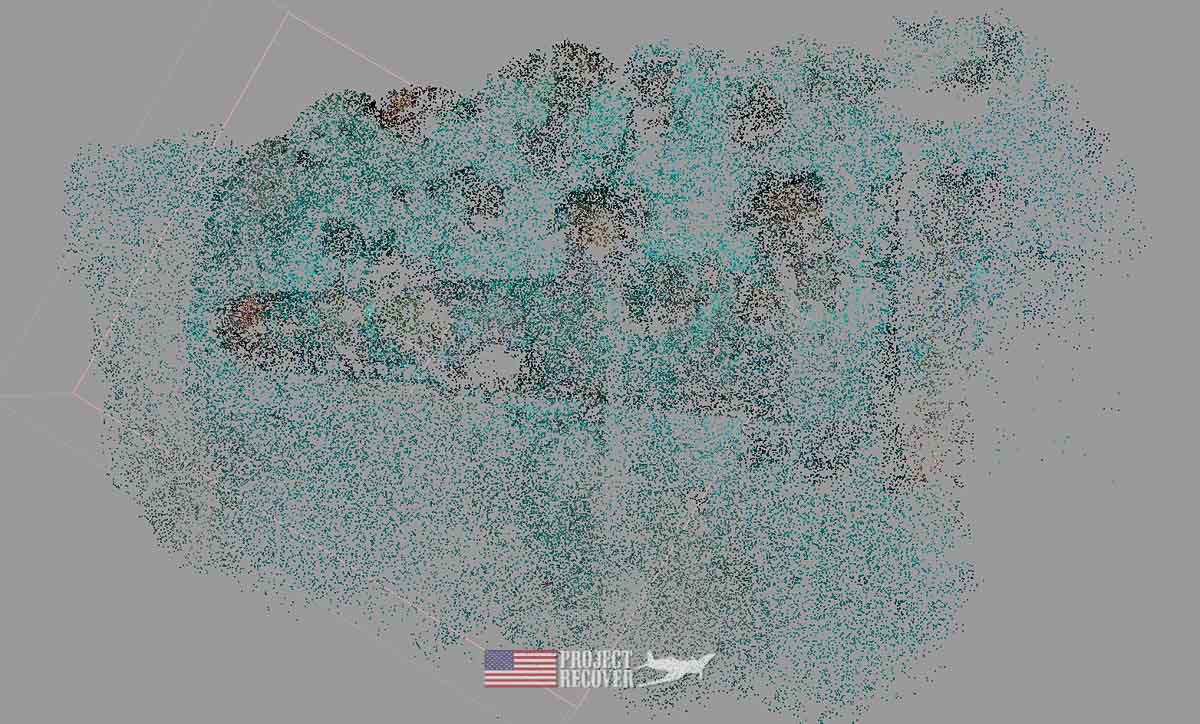

3D Modeling:

Learning to document an object in video for 3D modeling is something completely new to me, and I absolutely love the challenge. To create a 3D model requires cutting-edge technology. The program is powerful and requires lots of computer power to stitch images together. Every aspect of the shoot is crucial. Consistency is key. The distance to the object, camera angles, and the lighting all affect the final image.

After shooting it’s off to learn the 3D modeling program. I shoot the video, then pull still images from it. The still images are loaded into a stitching program. It requires tons of computer power, that we do not have. Even using the lowest possible settings, it still takes hours to get a glimpse of how we are doing. After waiting hours and tying up our computers, the images still require a lot of manual manipulation. It is all a learning process. Every site is different. Conditions change. All affect the documentation and the final image product.

The final images are used for a complete 3D rendering of the wreck. This 3D Model is included in the mission final report and makes its way to other researchers, museums, and education use. The ability to study images virtually gives others a much clearer view of the wrecks we are documenting without ever being on location.

The Taka Experience:

By day two we begin to realize how truly blessed we are as the Solomons MIA search team. Winds are light. It’s not as hot, muggy, or buggy as we had imagined, and the Pacific Ocean is calm, glassy, and fast becoming referred to as “the pool.” The Taka’s large stern platform is absolutely amazing. We got to step off the edge into a calm ocean and free fall 100 feet to our working site. After each dive, we debrief and plan for the next dive. Then it’s on to downloading, reviewing, and note-taking.

Food starts with the sunrise and the whining of tender wenches lowering our zodiacs into the water. Then it’s on to coffee, fresh fruit, and our first dive. After our first dive, we are back on board for our second ‘breaky”, a real home-cooked hot breakfast. We debrief all the teams’ dives. We work together to recall every minor detail of the wreck, filling in the blanks on a sketch of the wreck.

We are all working on something. From notes, searching manuals, learning programs, downloading media, there’s little time for anything else. Our bottom time requires a long topside interval, and the working time flies. Before we know it, we are on a 20-minute call for the next dive.

During all of this, the Taka crew is in full support mode. From food to air supply we are always in a state of readiness. The large dinner hall supported all our meeting and debriefing needs with a large table, coach, and two large screen TV’s for viewing. Crew members were always on hand and ready to help.

After the second dive, we repeat the flow, add in our plans for the next morning’s dive, have dinner, and settle in for the night reviewing sonar imaging. Then it is off to bed for everyone. We rise and set with the sun and are rocked to sleep every night to the hum of generators and on the gentle hands of the Pacific Ocean.

Back In The Water

Our camera team’s mission is to use what we learned on the left wing to begin documenting the right wing. At over 50 feet, both wings are monsters, covered in massive coral, anemones, and fish, some of which can kill us. The coral and fish life are amazing. I get to see all of it close up, as my job is to film every inch of the wreck.

My video system uses light. At 100 feet there is not much light. Adding light fills the view with the real color of the ocean. My path is filled with vivid reds, yellows, oranges, blues, and the list goes on. All of this spectacular view is just a few feet in front of me and my lens.

The sonar team took it much farther out and patiently waited for the arrival of the local EOD police team. They were expected to bring a side scan sonar and will work with us for a few days. The side scan sonar took on the larger search area using a towable sonar device that scans sideways. This enables large search areas in a short amount of time. The real work is in watching all the footage looking for signs of a find.

The handheld sonar is a major piece of high tech equipment requiring currency, patience, and study. It’s new to the team. Jeff’s first task is to relearn the beast and make it consistently operational with the touch of a button.

The archaeology team begins their meticulous documentation of the wreck. Our entire team, and this Solomons MIA search mission, looks at the wrecks as more than a hunk of metal. They are tombs of our fallen. That is our starting point and framework for diving and documenting the wreck. Little is disturbed as they painstakingly hand search the site using noninvasive archaeology techniques. They leave no trace of their visit while looking for evidence.

Finishing Up

By day three, the days are a blur. We are settled into this Solomons MIA search mission, each with their our own objectives and tasks.

We had one more diving day on this wreck, and everyone could feel the pressure. I had holes to fill in my own documentation. The sonar team had not found the missing piece and were now working with the local EOD and side scan sonar team. The archeology team was now pressed to complete the survey and begin written reports. The dives were made with completion in mind. We each wanted to be sure to get what we needed in the way of footage, sonar coverage, and survey objectives.

Around this time we are invited back to the island for some cultural education. The entire village came out. The children presented a long and well-rehearsed compilation of dances passed down for generations. The mood was fun and lively adding to our experience of the these Pacific islands. Again the light, friendly, and caring nature of the islanders leaves its impact.

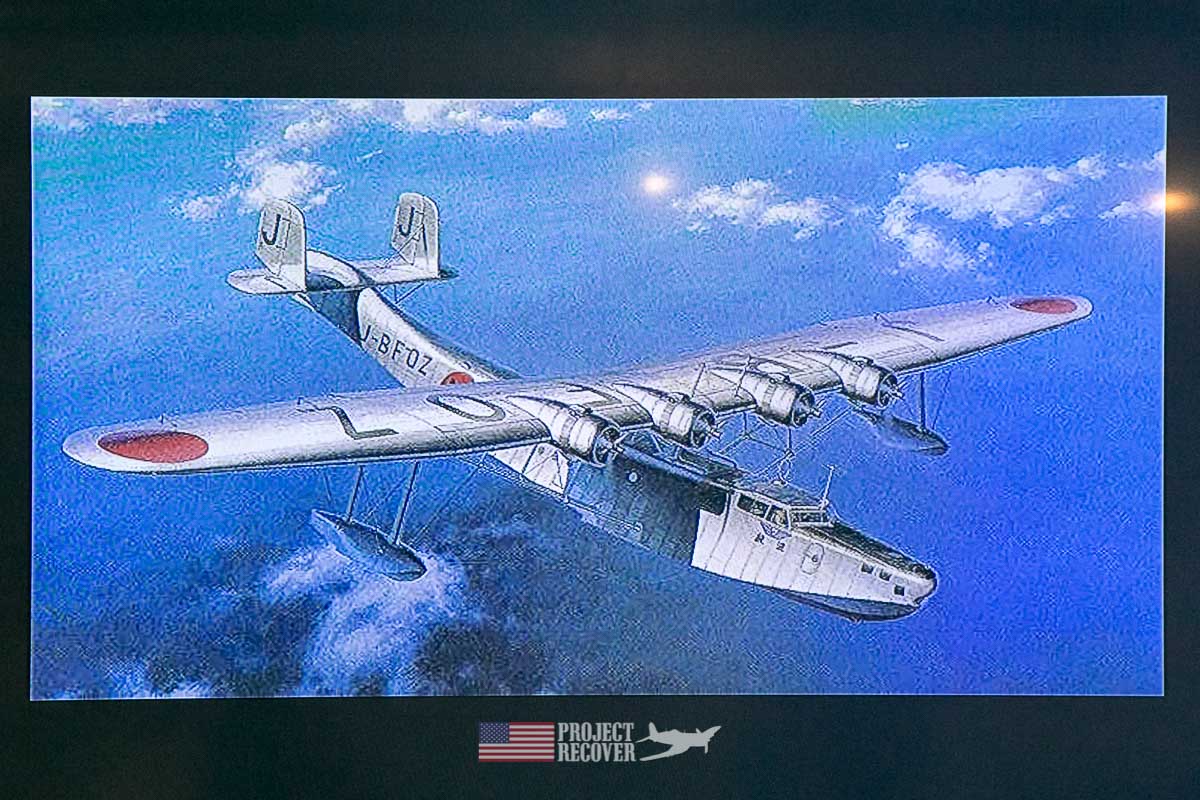

Japanese Wreck

Our next dive is a known Japanese Kawanishi H6K flying boat, called a Mavis in the US and UK, in an established harbor. It is where some of the fiercest island battles of WWII took place. It is a four-engine plane at 100 feet deep. It is loaded with guns, ammo, and a case of saki all sitting at the ready as if just days ago. This dive was a welcomed break from the intensely focused work dives of this Solomons MIA search mission. Visibility was ok for a harbor, and the sunset light gave a ghostly feel. We all swam every inch of the wreck taking in as much as we could.

After dinner, we pulled anchor and started heading back to port. We have intel on a possible MIA wreck. Our information is sketchy and dated. The possible target is located in a harbor used to traffic and anchor drops over the years. It is possible the wreck has moved or been removed. For the better part of the day, we use best guess GPS points and sonar pattern searches to no avail. The water is heavily polluted. The sonar team was unfortunate enough to enter the water as an oil slick moved through. Before day’s end, we call the search off and head to our next waypoint.

The next target is another known wreck. Our mission is to document it. The target is located in a harbor close to shore and our home port. Conditions were always marginal. It took till sunset to find it with visibility at 3 feet or less. Once marked, we settled in for a hot meal, debrief, and started packing to leave the Taka.

After almost a week with the Taka Crew, goodbyes were hard. The crew made this Solomons MIA search mission the best it could be. Our trip was different than most of their tourist dive trips. We all got to know each other. The Taka crew worked hard to be a part of our success. The crew really helped in all areas of our trip. From staying fed, hydrated, help with gear, navigation, getting in the water, and getting out of the water, our Taka crew was the best. We had made new friends and saying goodbye was difficult.

On Our Own

Our time on the Taka was over, but we still had another target marked. All we needed was a ride. Luckily, Ewan knew an old friend running a dive operation right by our hotel and five minutes from the target. A beautiful twin engine, all metal, center console diving boat that was fast and efficient.

The next morning we dropped our stuff at the hotel, then Dan and our camera team headed out. It took five minutes to get to the site, find the marker, anchor, and get in the water. Visibility was maybe 15 feet. I struggled with lighting and the camera settings. The wreck is covered in garbage and silt. From plastics to glass and aluminum, much of the wreck is covered or buried. I give it all I had with max bottom time and then we surfaced. Ewan took tons of photos and documented all he could, writing tons of information for his notebooks.

After reviewing my own footage I wasn’t confident and called another dive. After a long surface interval, we made it back to the site late in the day. The tide came up and it took a while to find the marker barely below the surface. Once in the water, we took the freefall to the wreck. Visibility was down to 3 feet or less. It was a pointless dive for shooting useable video, and we called the dive. Our time was up. We had to head back, pack up and prepare for our island exit strategy.

It was disappointing, but the best we could do with the time we had. It’s a hard site to document, and it was obvious we would need a couple days with dives only in the morning. The potential for this to be a true MIA site is evident and requires further attention.

The next morning, it’s time to prepare to leave. We have a final meeting by the pool for a trip debrief. It is our last meeting as a team for this mission. The night is filled with packing, downloading, digital copies, equipment cleaning, drying, and the task of preparing to fly.

Summary

The Solomons MIA search mission’s focus was to document the primary target. We did that with the time allotted. We struck out on a lead, and found the third target but did not fully document it. The latter two were hopes, additions, steeped in the commitment to bring our MIA’s home. The fact is, there is a LOT to cover in the Solomons. We could spend seasons there.

And this is what a trip looks like, how it develops and what we are actually doing. Every trip is a little different, and this is a good overall view of the outsider looking in. Make sure to check out the Project Recover’s website for more information and updates. Want to see more photos? Check out the entire Solomon Islands MIA search photo gallery.

Thank you for your support and interest.

Feel free to leave your comments or questions below.

Harry Parker, Photographer

Read more posts related to Project Recover’s Search for MIAs in the Solomon Islands:

- June 2018 – Post 1 – Team Heads Out to Find Solomon Islands MIAs

- June 2018 – Post 2 – Scuba Diving MIA Crash Sites

Read posts related to Project Recover’s Search for MIAs in Palau

- June 2017 – Charlie Brown – Mission to Find the MIA and Executed

- June 2017 – Glenn Frano – Searching for Executed WWII MIA and Innocents in Palau

- June 2017 – Derek Abbey – Palau WWII POW search

- July 2018 – Execution of WWII POWs and Innocents in Palau

- filming a SBD WWII underwater wreck during Solomons MIA Search

I was one of the lucky ones – my father came home. But for all those wives, parents and children who weren’t so lucky, I thank you all for taking the time, energy and determination to complete your mission! I appreciate you keeping us informed and include photos in your posts.

It is with great anticipation to receive your mission updates. Being former military this is the type of project I could devote myself to, but moreover 20 years earlier. Failing health would only cause me to be a liability to your efforts, but none the less

I can visualize myself being with you all in recovering our lost hero’s. I wish you all well in your endeavors and I hope you find

and retrieve all our Brothers.

Thank you for the thoughts. Keep up the visualization of pushing our efforts in the jungles and oceans of the world!

I wish the photos had explanatory captions.

We will work on that.

After seeing your photos of the beautiful, peaceful blue waters, blue sky and lush vegetation, it is hard to imagine the fierce battles occurring off the Southern Solomon Island of Guadalcanal in late 1942. My Uncle, then Marine Col. Christian Frank Schilt, a naval aviator, described in his oral history interview what it was like: “It was nip and tuck there, whether we were going to keep the place or not because the Japanese were sending down so many planes and big ships. But we finally got enough planes and we knocked down so many Jap planes at Savo Island … well, one day, I saw 90 Jap planes fall. One day. After that we had it under control.”

I have often wondered where those planes and pilots are today.

Thanks for the perspective from your Uncle.

A lot of history there and so much more to find.